Combs have been a favourite shore find of mine for years. I like that they’re ordinary, personal objects, as well as one of our oldest tools. The earliest known comb was carved from bone around 8000 years ago, and the design has changed little since the Bronze Age. Over millenia, they’ve been made of everything from gold, horn and tortoiseshell to ivory, wood and plastic.

In the photograph above, the central comb was carved from bone in the 17th or 18th century (with thanks to the Finds Liaison Officer at the Museum of London). Most of the others are injection-moulded plastic.

I was delighted when I found this bone comb on the Thames foreshore in central London, in part as it was close to where my family lived in the mid 1800s. From its condition it had only recently eroded from the riverbed, having been beautifully preserved for three or four centuries by the anaerobic Thames mud.

Fragments like this, often boxwood or bone, are fairly common finds on that stretch of the river. The fine-toothed side was used on elaborate Elizabethan and Georgian hairstyles to remove gums and pomades (perhaps made from overripe apples, perfume and lard), and also to tease out nits. When 82 similar combs were found on the Mary Rose – a Tudor warship that sank in 1545 – several still contained nits that were almost 500-years-old.

The combs above are all plastic and were found on Cornish beaches. Some have drifted at sea for years or even decades, while others wash out of the sand if gales coincide with high spring tides. They are usually left high on shore amongst the strandline flotsam, and I began collecting them years ago, finding something poignant in their faded colours and broken teeth.

Yet a few don’t float. I find these further down the beach at low tide, where waves push the seabed debris ashore. These are older and heavier, making a hard, brittle sound if I knock them together, with some made from early synthetics like Bakelite and celluloid.

Although hard to imagine now, those first plastics were conceived as a means of protecting the natural world. The early appeal of celluloid, for example, lay in its ability to mimic limited and expensive natural materials such as ivory and tortoiseshell. Often marketing their new wonder material as ‘French Ivory’, manufacturers claimed it would ‘no longer be necessary to ransack the earth in pursuit of substances which are constantly growing scarcer.’

By the 1950s, combs were made from injection-moulded plastic. In an illustration of rising productivity, a photograph in the Times showed father and son combmakers standing beside their respective daily output of combs. Beside the father is a neat stack of 350 celluloid combs, whereas his son is surrounded by the 10,000 plastic combs a machine could produce in a day.

Today, they are common finds amongst the strandline plastic.

.

There is more on the ‘Travelling Museum of Finds’ here

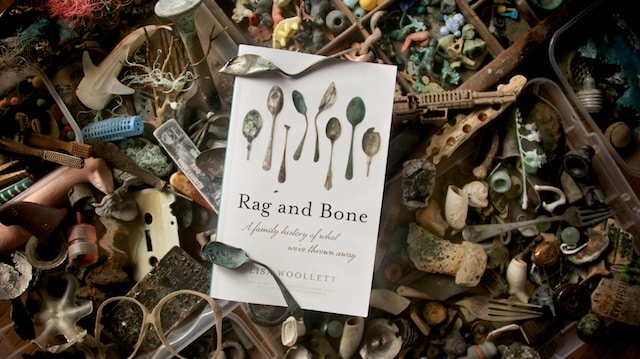

and reviews of Rag and Bone (John Murray, June 2020) here

The hardback is available to pre-order at Waterstones, Foyles and Amazon. Best of all, particularly in these difficult times, do use independent bookshops. Or try Hive, which allows you to support them.

.

If you’d like to follow the blog please give your details below.

To share the post: