In Europe, the toothbrush remained a luxury until the late 18th century. The most expensive had badger-hair bristles and handles made from ivory, mother-of-pearl and silver. Yet despite a steep rise in the consumption of sugar, most people in England were still using ‘chewing sticks’ or rags with an abrasive such as salt, brick dust or soot.

In 1780, William Addis began manufacturing bone toothbrushes in London’s East End. His eureka moment is said to have come while he was imprisoned for rioting: inspired by a broom in his cell, he made his first toothbrush by drilling holes in a bone left over from a prison meal.

Addis began production soon after his release, with the handles carved from cattle thighbones (their rounded ends often saved for the button makers). Early bristles included hair from horses’ tails and goats, attached by local women in their homes as piecework. But pig hair proved to be better, and the very best from the necks of Siberian wild boar.

By the 1840s, mass production of bone and boar-hair toothbrushes was in full swing, although it was still common for families to own one to share between them all (and Victorian families were large). The handle’s traditional ‘hanging hole’ was to help the bristles dry between uses, which was considered more hygienic.

Although the simple design barely changed, the shift to synthetics began in the 1920s and 30s, with celluloid handles and then nylon bristles. By the 1950s toothbrushes were plastic, often the transparent coloured acrylics that remained popular for decades. In the photograph above, the one on the far left – after decades in the Thames – still has the greenish copper wire that once held the bristles in place.

Like celluloid combs, some of the older acrylic toothbrushes sink, and I find them when storms push the seabed debris ashore. Yet most plastic handles float, so turn up on the strandline – occasionally sprouting colonies of goose barnacles (below). In the past, these extraordinary creatures attached mainly to driftwood, but now I find them on everything from plastic bottles and fishing gear to flip flops.

Today, few of my flotsam toothbrushes are of that simple original design, which dominated for more than two centuries. Instead I find a bewildering variety of fat, ergonomically designed handles made from mixed plastics and rubbery grips, meaning they are almost impossible to recycle.

I began finding ‘floss picks’ (above) on the strandline years ago, although at the time I didn’t know what they were. It turned out they are elaborate toothpicks – many also snap in half to create a more traditional toothpick – which have an ancestry stretching way further back than the toothbrush. Toothpicks may even be older than our species, with some Neanderthal skulls showing marks that appear to have been made by rudimentary toothpicks, or even flossing with tough blades of grass.

In the tens of thousands of years since, humans have made toothpicks of everything from fish bones and walrus whiskers to ivory and sharpened goose quills. In 17th century Europe, fashionable toothpicks made from jewel-encrusted gold were shown off after sumptuous meals. Today, the plastic floss picks I find on beaches can be bought in packs of 250, and are designed for a single use.

.

There is more on the ‘Travelling Museum of Finds’ here

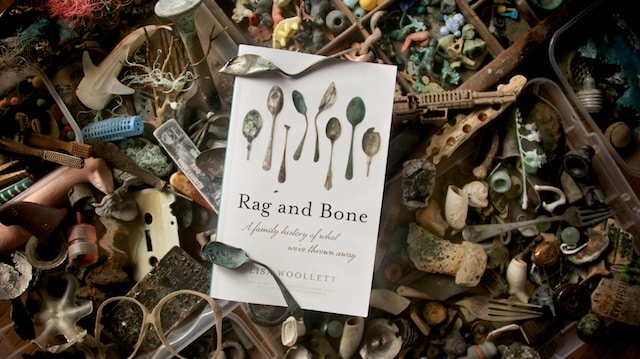

and reviews of Rag and Bone (John Murray, July 2020) here

The hardback is available to pre-order at Waterstones, Blackwells, Foyles and Amazon. Best of all, particularly in these difficult times, do use local independent bookshops. Or try Hive, which allows you to support them.

.

If you’d like to follow the blog please give your details below.

To share the post: